Unless you’ve been under a rock, you know that Outer Banks delivered one hell of a cliffhanger by the end of Outer Banks Season 4, and to say people aren’t pleased would be an understatement.

No, we’re still not over the decision to write out JJ Maybank, the Pogue Prince, if you will, and we never will be.

And the way they opted to do so has been so asinine that it’s left many of us wondering if we even need a fifth and final season of one of our favorite series.

Here’s the thing: there is a reason why Outer Banks catapulted to acclaim as it did, despite serving as some random teen series with virtually unknown talent that appealed to people of all ages and walks of life.

Outer Banks had the fortune of premiering at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The entire world seemed to shut down in an unprecedented manner, like something from a horror movie or post-apocalyptic series.

The US shut everything down on March 15, 2020, and approximately one month later, this delightfully beachy escapist series premiered on April 15.

One month in, we were all trapped in the house, some of us climbing up the walls, bingeing through everything that every streamer had to offer, longing for any sense of escapism or connection.

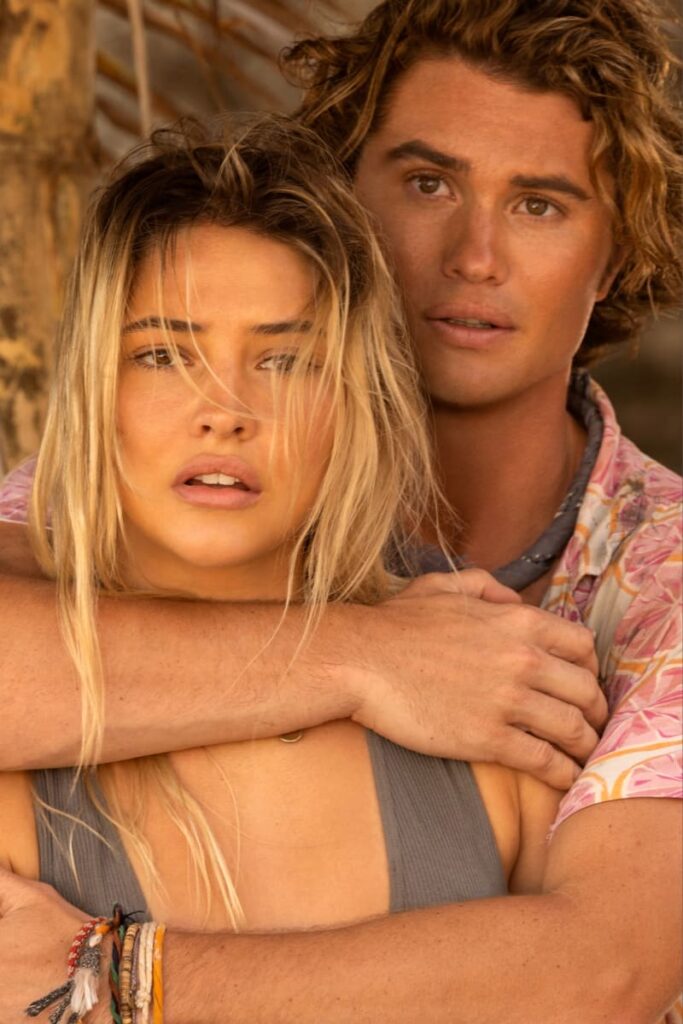

And we found it in this little series that featured a diverse group of teenagers from the Outer Banks community where differences were stark but freaking friendship overcame everything.

With its dusky orange and yellow filtered shots, we could escape to the beach and lose ourselves in the setting of warm sand, cool waters, and what appeared to have been the finest of weed.

We won’t judge you for your recreational vices, especially during that particular time.

We always discuss escapist television and the longing for it so much that it hurts.

For the past decade and a half, far too many series and just television as a medium shifted away from the type of lighter fare and exciting, fun stories in favor of darkness, grit, and morally ambiguous or depraved characters and storytelling.

To say that Outer Banks was a breath of fresh air would be the understatement of the century.

It was quite literally like a breath of fresh air, our connection to the world that we once knew, access to the type of lifestyle and adventure that we aspired and longed for from the confinement of our rooms, or worn in couches.

We didn’t have to tune into every press conference or daily update about the state of a deadly virus sweeping across the globe, nor did we have to scroll on our phones to see worn-out first responders crying or an endless list of names belonging to those who had succumb to something we still didn’t fully understand.

Instead, we had John B narrating what felt like an exceptionally simplistic life with his close friends and the promises of an adventure.

As some mysterious virus ravaged its way through the globe, it was one of the few times when we all felt like the underdogs.

After all, it didn’t discriminate nor distinguish between race, gender, age, nationality, or socioeconomic status.

So when Netflix dangled a lifeline to viewers in the form of impossibly pretty teenagers seeking adventure while simultaneously bucking against a system, socioeconomic and class structure that kept them down, it didn’t matter who you were or where you came from—we were all Pogues.

Outer Banks was strangely hopeful despite depicting one of the few consistent explorations of power, caste, and class disenfranchisement we’ve seen on television in a while.

We’ve already delved into the lack of Working-Class Heroes on television and how an obsession with family dynasties like Succession‘s Roys and Yellowstone‘s Duttons has dominated and surpassed the standard upper-middle-class suburban status of nearly every “normal” character on television.

Somehow, Outer Banks balanced this focus on the perpetually poor and disenfranchised by highlighting the “against all odds” spirit of its primary characters.

Yeah, Pope, John B, and JJ constantly had run-ins with the douchey Kooks, resulting in physical altercations and child’s play foolery. Still, the Pogues always persevered through the power of found family, optimism, and profound love.

Outer Banks’ friendship and the Pogues’ inability to stay down and out for long propelled the series forward and contributed to its popularity and appeal to the audience at large.

We kept coming back because regardless of how absurd the plot points and just how often the Pogues would come close to winning it all only for treasures, security, and whatever else to slip through their fingertips, the Pogues’ indefatigable spirit was inspiring and that friendship was everything.

The “realism” of Outer Banks stopped at the class divide as a jumping-off point for so many plots.

We had poor teenagers globe-trotting in search of treasure without even two nickels to rub together, let alone passports.

They’ve each defied death a half-dozen times, and we went along with that because the Pogues are distinctly human and compelling characters, but this simply never was the type of show in which the Pogues died.

We were okay with that—this unspoken agreement.

It didn’t matter that they routinely cheated death; this was simply a byproduct of a silly little treasure-hunting show that never pretended to be a prestigious piece where all the plots made sense.

Most of Outer Banks’ plots are ridiculous, but that is part of the show’s charm.

It’s what it promised to be when it crashed into our lives like the perfect surf swell in the middle of a pandemic, operating on pure vibes and cast chemistry.

With its instant success, it was abundantly clear what worked about the series, why the audience responded so well, and the pathway toward appeasement.

It’s the unspoken contract, if you will, between viewers and creators, part of the copacetic relationship that makes the entire process work.

Outer Banks was never devoid of darkness: it has so many murders that it could compete with your average procedural.

John B’s displacement as an unhoused orphan on the wrong side of the tracks could get incredibly bleak, right along with his various near-death experiences.

JJ’s backstory, both the original and whatever the hell this revamped one is, was tragic but also so real.

JJ Maybank joins the ranks of coveted teen heartthrob characters from poor backgrounds who thrive against all odds and provide hope.

Think of the Shawn Hunters, Pacey Witters, Tim Riggins, and Ryan Atwoods.

For many of us Millennials, our teen-based stories were riddled with them, and we cherished each one.

They had universal appeal, notably because, among a sea of characters who probably came from stable means, these characters resonated the most across the board, regardless of one’s walk in life.

Pope Heyward is perfectly representative of the “great hope” character on whom everyone pins their hopes and dreams—the one with a real shot of breaking through the barriers and actually ascending in the “pull yourselves up by your bootstraps” American dream history has sold us on for centuries.

These were all characters who truly embodied the “underdog” status, and thus, every win was our own, and every loss sliced through us as if they were our own loved ones.

Despite the tumultuous times with them all, they were always fun to watch because there was a comfort in these characters daring to dream, being bold, taking risks, and being themselves unapologetically while navigating a world hellbent on beating them down.

That’s why Outer Banks was always innately comforting and hopeful, even when storylines and plots became dark.

But then the series lost sight of that.

Never actually giving the Pogues a win until the end of Outer Banks Season 3 was particularly hard to process.

Maybe it was realistic that life constantly dealt the Pogues shitty cards, and no matter how hard they tried, they could never find their footing or a moment’s peace.

At some point, the relentless beating down of the characters showed that the series strayed from its premise and positive messaging.

By season three, trauma dumping on each character practically became an Olympic sport.

John B wrongfully going to jail and standing trial became finding out his father was actually alive and relatively crappy before dying.

Sarah’s “wrong side of the tracks” love story with John B eventually becomes a horrific house of horrors situation pulled from a V.C. Andrews novel.

The men in her life heap unspeakable traumas upon her that she merely takes and carries unresolved.

Pope’s aspirations go up in smoke time and again as his career desires slip between his fingers right along with his family’s legacy treasure in a world where wealthy, White elites steal and profit off the pain of the disenfranchised.

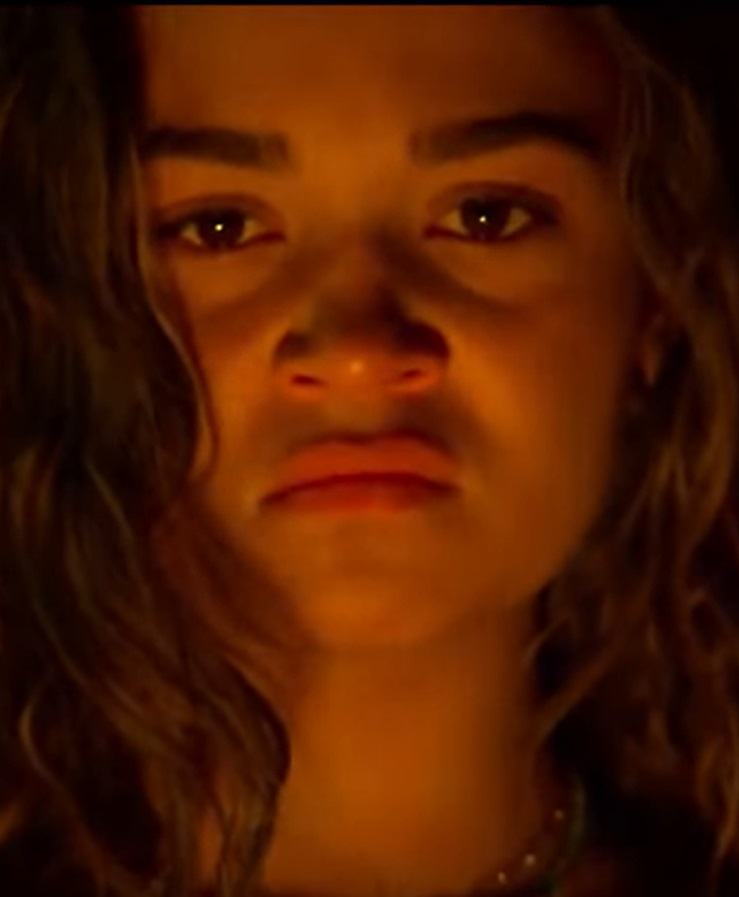

We saw a spirited Kiara cast away to a horrifying reform school; you know, the type full documentaries are made about because of the longstanding abuse of children and teens deemed a problem.

And things were no better when her parents disowned her.

Then there’s JJ, who had so many atrocities stacked against him; it’s why his eventual fate still reverberates across the internet as fans of all ages ask the same question over and over again: Why?

Imagine for a second if Boy Meets World killed Shawn Hunter.

I’m not the most tapped into all things Gen Z, but I know that losing JJ is the equivalent of that.

And while there is plenty of beef for how showrunners handled Shawn Hunter across two series (including a mishandled ship; the Shawngela to Jiara pipeline is real), at least there was enough cognizance of the audience to know that killing him wouldn’t fly.

There’s a reason why JJ Maybank was the heart of Outer Banks.

The series understood this enough even to reference him as the “Poguest Pogue.”

He represented the rose that grew from the concrete, an irrepressible spirit who could never get counted down or out.

JJ is emblematic of the hope that one’s circumstances or how much life could be stacked against a person didn’t matter; life was still worth living.

Even as the walls were closing in, the world could still be one’s oyster, and there was a silver lining: one could overcome one’s circumstance, find love, friendship, and happiness, and still thrive.

With JJ, there was a sign that one still has a shot when everything around them seems bleak or tragic.

It embodies the message Outer Banks sold us on when it became a comfort show amid a pandemic and created comfort characters like the Pogues who resonated and inspired.

And then they went back on it; for what? Kicks, shocks, thrills?

Was it some misguided attempt to be something other than what it was, screwing up a good thing rather than sticking to what works?

We’ve seen live and in living color that the JJs of the world, more often than not, end up in a jail cell, a grave, or trapped in a cycle of poverty and generational trauma.

What does it say that even on a series that presents Outer Banks as “paradise on Earth,” the JJs meet the same fate in fiction, too?

Have things become so dire that we can’t hope or escape anymore?

Considering how challenging Outer Banks Season 4 was well before that tragic cliffhanger ending, is it safe to say that they should’ve left things with Outer Banks Season 3’s finale?

We had a time jump, the Pogues finally getting a treasure (meager amount undisclosed), friendship, happiness, love for all, and the promise of more adventure.

If we’d rather they had suspended the Pogues in time at that moment instead of setting up a fifth and final season of vengeance, trauma, and grief, then Outer Banks’ final season has its work cut out for it.

We got a fifth and final season to say goodbye to the remainder of these characters and this comfort show.

Unfortunately, it comes at a cost the audience never wanted to pay, and the series simply can’t handle.

Over to you, OBX Fanatics.

How do you feel about Outer Banks now?

Will you be returning for the fifth and final season?

Do you think Outer Banks lost sight of its premise?

Sound off below and let’s discuss it all.